In 1987, forensic DNA analysis made its first appearance in a US courtroom. Originally known as "DNA fingerprinting," this type of analysis is now called "DNA profiling" or "DNA testing" to distinguish it from traditional skin fingerprinting.

Even though it is used in less than 1% of all criminal cases, DNA profiling has helped to acquit or convict suspects in many of the most violent crimes, including rape and murder.

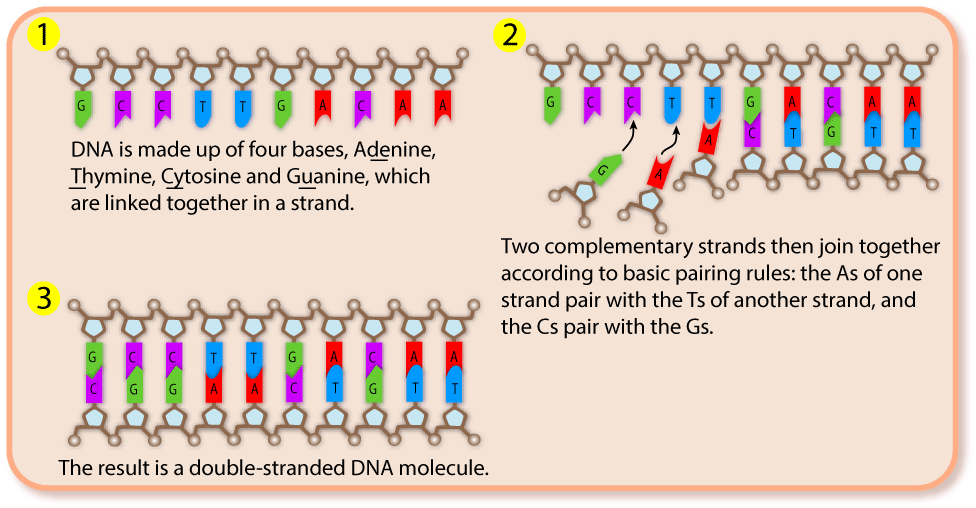

Almost every cell in our bodies contains DNA, the genetic material that programs how cells work. Any two people share, on average, 99.9% of their DNA, meaning that only 0.1% of your DNA is unique to you! The only exception is identical twins, who share 100% of their DNA.

Each human cell contains three billion DNA base pairs. Our unique DNA, 0.1% of 3 billion, amounts to 3 million base pairs. That's more than enough to provide a profile that accurately identifies a person.

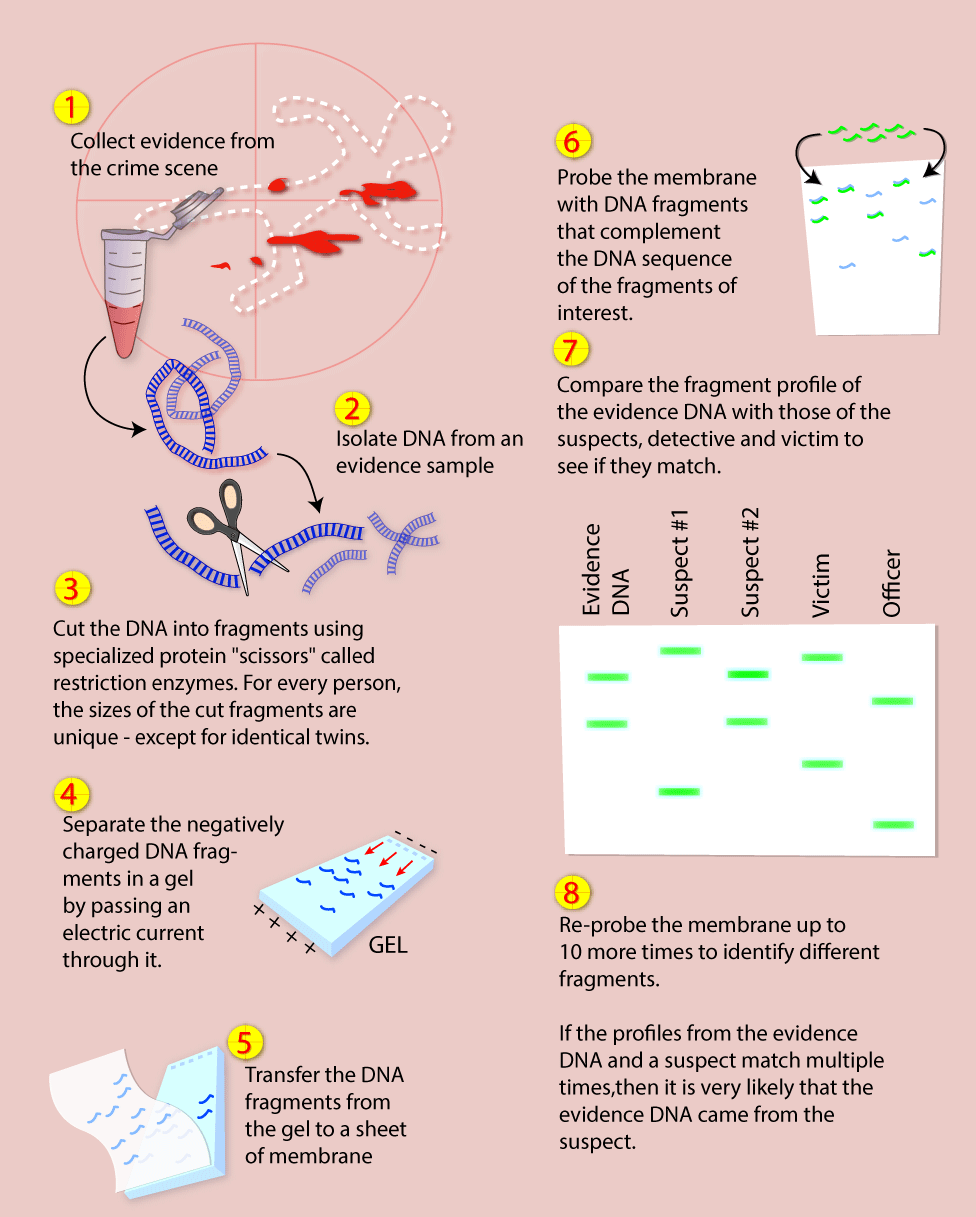

DNA is often left behind at a crime scene. It is present in all kinds of evidence, including blood, hair, skin, saliva, and semen. Scientists can analyze the DNA in evidence samples to see if it matches a suspect's DNA.

On the right, you can see how DNA evidence used to be collected and analyzed. In its early days, DNA analysis required an evidence sample at least the size of a dime. Today's techniques can amplify the DNA usingPCR, making millions of copies from tiny amounts of evidence, such as the saliva from a cigarette butt. This approach is also helpful for analyzing poor-quality DNA in evidence samples collected from dirty crime scenes or in very old samples.

Unrelated individuals have three million DNA bases that differ between them, but blood relatives have fewer differences. If the DNA profile from a piece of evidence is similar—but not identical—to that of a suspect, officials may investigate blood relatives of the suspect.

Forensic investigators take many precautions to prevent mistakes, but human error can never be eliminated. The National Research Council (NRC) recommends that evidence samples be divided soon after they're collected, so that if a mix-up were to occur, there would be backup samples to analyze.

To detect possible contamination of DNA samples during collection or handling, evidence DNA profiles are typically compared with those from detectives at the crime scene, the victim, a randomly chosen person, or a DNA profile from a database. Each sample is assigned a code, and testers don't know who the samples came from.

The NRC recommends that forensic DNA analysis be conducted by an unbiased outside laboratory that maintains a high level of quality control and a low error rate.

It is easier to exclude a suspect than to convict someone based on a DNA match. The FBI estimates that one-third of initial rape suspects are excluded because DNA samples fail to match.

Forensic DNA is just one of many types of evidence. Investigators also look at other clues, such as motive, weapons, alibis, and additional evidence linking a suspect to the crime scene. When multiple lines of evidence tell a consistent story, investigators can be assured that samples from a particular suspect were not planted, either on purpose or by accident, at the crime scene.

The Innocence Project at New York's Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law aims to exonerate prisoners wrongfully convicted of crimes. The project uses DNA profiling evidence to support the re-evaluation of criminal cases. But DNA evidence alone is not enough to get a person out of jail: the case must be re-examined by a judge, along with lawyers representing both sides of the case. Since 1992, the Innocence Project and others have used DNA evidence to exonerated over 300 prisoners, including eighteen who were on death row—one of whom was only five days from execution.

While some states will reconsider cases with compelling DNA evidence regardless of when the trial ended, several states restrict the time for post-trial submission of DNA evidence to six months or less. And unfortunately, the evidence from some cases has been lost or destroyed, making DNA analysis impossible. The Innocence Project seeks to reform the criminal justice system in ways that will improve access to DNA testing, improve evidence preservation, and permit re-evaluation of DNA evidence in closed cases.

DNA profiling can be a powerful tool in criminal investigations. Its success in the courtroom depends upon many factors, including:

When used correctly, DNA profiling is a powerful forensic tool. It can be used to quickly eliminate a suspect, saving time in searches for perpetrators. And it can provide compelling evidence to support a conviction and, most importantly, reduce the chances of a wrongful conviction.

This work was supported by Science Education Partnership Awards (Nos. R25RR023288 and 1R25GM021903) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The contents provided here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.